A recent subtext in the debate on health care reform has been about Medicaid’s alleged failure to provide its enrollees with access to care – the argument goes that the parents and childless adults who would be added to Medicaid as a result of leading proposals would mean that 15-18 million people would be dumped into coverage where they wouldn’t be able to see a doctor. As often is the case in Washington, the facts are considerably more nuanced than the talking points.

First, research is very clear that Medicaid has increased access to care and reduced unmet health needs for both children and adults. In fact, in terms of primary and preventive care, access to care in Medicaid is approximately equivalent to that in private insurance. Access to care issues in Medicaid are more likely to arise in certain specialties (most notably such as access to dentist care) and in certain geographic areas and they most certainly exist. But having Medicaid has been critical in improving low-income children’s access to needed care.

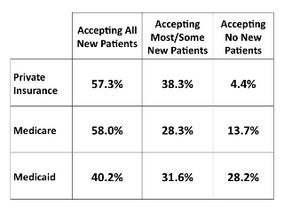

We’re all aware (perhaps from our own experience of trying to find a doctor who will take our insurance) that having an insurance card does not necessarily ensure access to care. I have virtually given up finding an internist that will take my Georgetown University Blue Cross plan. Doctors and hospitals pick and choose which insurance plans they’ll take. A recent Center for Studying Health System Change survey asked physicians whether or not they were accepting new patients. Their answers varied by patient insurance type:

Yes, there are more doctors who are not accepting any new Medicaid patients, compared with those accepting new patients covered by Medicare or private insurance. But overall, more than 70% of doctors are accepting at least some new patients covered by Medicaid.

Part of the issue with the slightly lower physician participation in Medicaid could have to do with lower reimbursement rates, which are about 72% of those paid in Medicare (and these rates are supposedly lower than private rates, but a true comparison is tough since that information is deemed “proprietary”).

Now, people may legitimately say that adding an additional 15-18 million people to the program is likely to exacerbate access problems. It is true that adding that many people into the system requires consideration of the program’s capacity to provide the care people will need. The most obvious solution — an increase in reimbursement rates.

And there may be hope on the horizon for just such a solution. Following the health reform summit, the President has appeared to embrace this idea. The House included a provision in its health reform bill for a phased-in increase in Medicaid reimbursement rates and it also seems to have bipartisan support (Sen. Grassley (R-IA) raised it as an issue at the summit).

Medicaid has been instrumental in meeting the health needs of millions of children and families, and through health reform, the program would be expanded to meet the needs of millions more. So let’s think about how to do that most effectively, but let’s not use the access challenges, which happen in private and public coverage alike, to become an excuse not to do meaningful reform.

Thanks to Martha Heberlein for helping with the research for this entry.