States are under tremendous pressure to continue to provide essential services even as resources dwindle, underscoring the importance of the 6.2 percentage point increase in the federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) in the Families First Coronavirus Response legislation Congress passed last month. Unfortunately, the health and economic consequences of this pandemic necessitate an even bolder response from Congress – the National Association of State Budget Officers echoed recommendations by the National Governors Association to provide a longer term increase in FMAP of 12 percentage points, including for Medicaid expansion. The Governors also called for eliminating the Administration’s Medicaid Fiscal Accountability Rule (MFAR), because as my colleague Edwin Park explains, much of the COVID-19 fiscal relief to states could be canceled out by finalizing it.

In addition to the budgetary challenges states are confronting, states also face the challenge of providing their residents with health coverage. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 response bills so far have not provided new coverage options for people, but have instead focused on paying providers for COVID-19-related testing and sometimes, treatment. To be clear, paying providers for these services is an essential part of an effective response, but people also need health coverage to ensure access to needed services and protection from unforeseen medical costs.

Fortunately, there are some coverage expansion options which predate the pandemic that states may want to consider taking up, even with constrained resources. The first and most obvious is for the 14 states that have yet to adopt the Medicaid expansion to cover parents and other adults to do so immediately. Another option is to waive the 5-year bar for lawfully residing children and pregnant women, known as the Immigrant Children’s Health Improvement (ICHIA) option. As of January 2020, 35 states have adopted this option for children in Medicaid, and 24 of 35 states with separate CHIP programs have adopted it for children in CHIP too. Take up has been less robust for pregnant women, with only 25 states adopting it in Medicaid and 4 of 6 states with separate CHIP coverage for pregnant women adopting it in CHIP (though some states that have not adopted ICHIA for pregnant women do offer coverage through CHIP’s unborn child option).

Coverage for ICHIA children is matched at the CHIP matching rate, regardless of whether the child enrolls in Medicaid or CHIP. The Families First legislation increased the Medicaid match by 6.2 percentage points, leading to a corresponding increase in the CHIP match of 4.35 percentage points. States that have yet to take up ICHIA for children should consider doing so now, especially at a time when health coverage is so critical and more costs will be borne by the federal government.

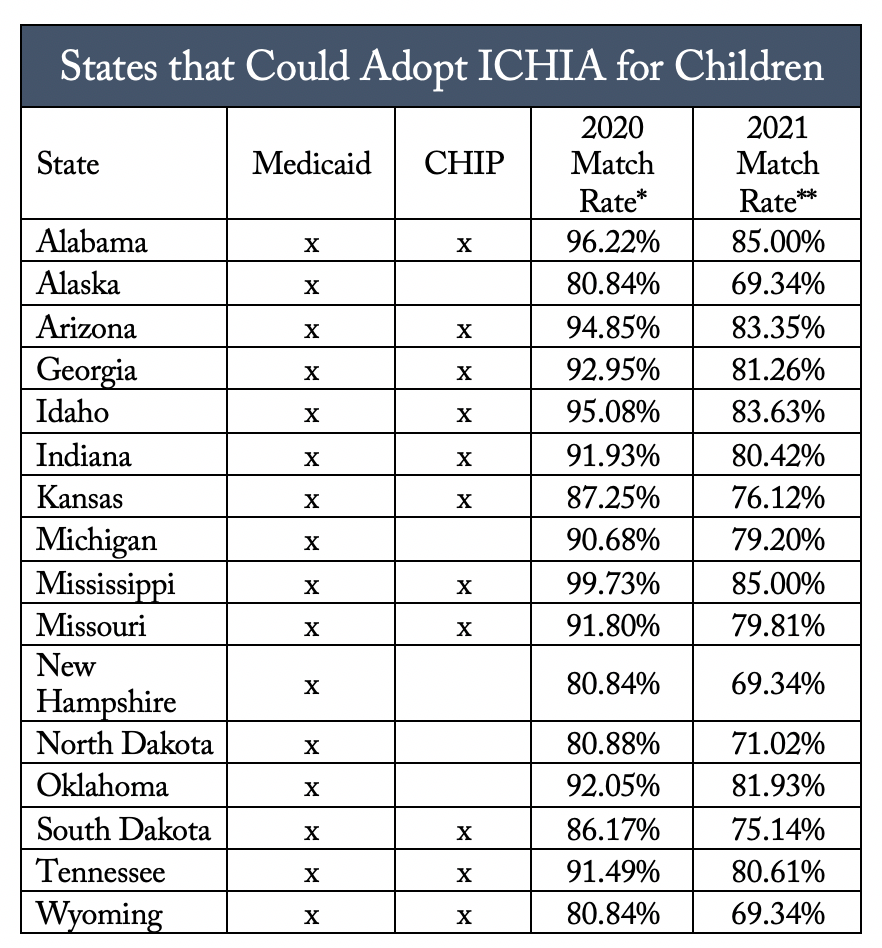

Of the 16 states that have yet to adopt ICHIA for children in Medicaid, and of the 11 states that have yet to do so in separate CHIP programs, 10 states would be eligible for a federal match rate at or above 90% for 2020 and 8 states would be eligible for a federal match rate at or above 80% for 2021.

Fewer states have taken up ICHIA for pregnant women in Medicaid, and the match for ICHIA pregnant women is linked to program enrollment (Medicaid match for Medicaid, CHIP match for CHIP). But even at Medicaid match, now would be a good time to take advantage of all the coverage options for pregnant women. It’s unclear whether COVID-19 impacts pregnant women differently, but expectant moms are worried about the risk to themselves and their babies and changes to prenatal care and labor and delivery policies. Taking up ICHIA for pregnant women (and/or the CHIP unborn option) would at least alleviate one concern by providing women with needed health coverage.

Clearly states have a lot to manage right now, but states should consider taking up all of the available coverage options to them in order to fill as many health coverage gaps as possible.